Part I: History – From the Early Field schools to the Contemporary

This is the first in a multi-part series examining the state of field schools in the U.S. While this series focus on archaeology field training in North America, many observations are relevant to archaeologists and students across the world as archaeology is a global practice.

Part I: This instalment explores the history of field schools in North America – from the first program to the present – and the forces and entities that contributed to their evolution. Understanding the historical context that shaped the current field school praxis can help those who seek careers in the discipline to choose the right program for their needs and career goals.

This instalment was sent to the CFS mailing list and is posted on the CFS Blog page.

The archaeology field school is a long-standing institution

within the discipline. Field schools were designed to introduce aspiring

archaeologists to the practice of the discipline and train them in the methods of

excavating and contextualizing the material record. As far as we know, the

first field school took place in 1878, when Lewis Morgan of Colombia University

took students for an exploration of Pueblo ruins in New Mexico (Fig 1). For the

next century, field schools became ubiquitous, and every major university held

at least one such program for its archaeology students (Fig. 2).

By the mid 1990’s, dramatic changes took place. As the world

entered the Technological Age, archaeology was a leader of technological adaptation

within the social sciences. Digitization and miniaturization of analytical equipment

made analytical studies well within the reach of archaeologists. Archaeological

research began to emulate the hard sciences, moving from a single scholar to a

team of specialists, all working together to study the past. At the same time,

universities were producing large numbers of PhD’s, overwhelming the limited

number of available academic jobs. This perfect storm increased the cost of

conducting archaeological research, but also made it more vital than ever. Graduates

of PhD programs could compete for positions only if they had active, ongoing

research projects and were constantly publishing research work. But how could

so many fund their research and stay relevant in the field? Field schools

became the solution, generating funds from student tuition to support research

work and generating student labor to support field work.

By the turn of the millennium, another change impacted

archaeology. Philanthropic funding shifted away from traditional giving,

including archaeology. The rising new class of wealthy technologists embraced impact

philanthropy – giving to issues that could be measured, had instant impact

and yielded significant social change. Government funding declined at the same

time as political winds rejected investment in basic science in favor of applied

sciences. Outside funding to support archaeological research declined

dramatically. This strong financial pressure brought entrepreneurship to the discipline,

especially in Europe, where funding was in extremely short supply. By the first

decade of the 2000’s, a number of independent organizations emerged, offering

not one, but a range of field school offerings using economy of scale to reduce

costs and attract students.

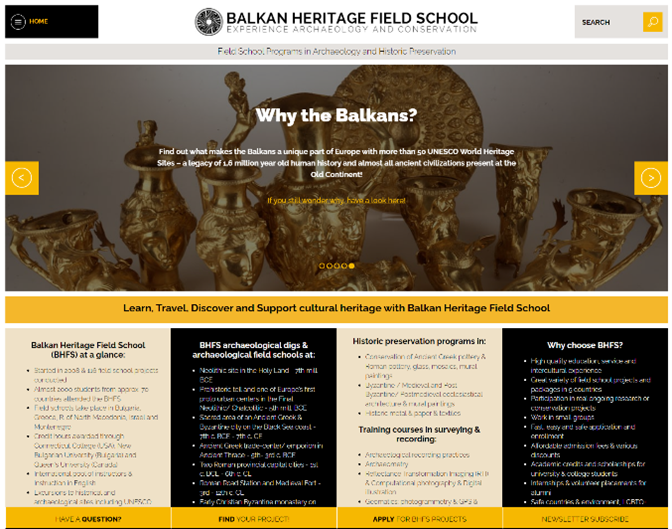

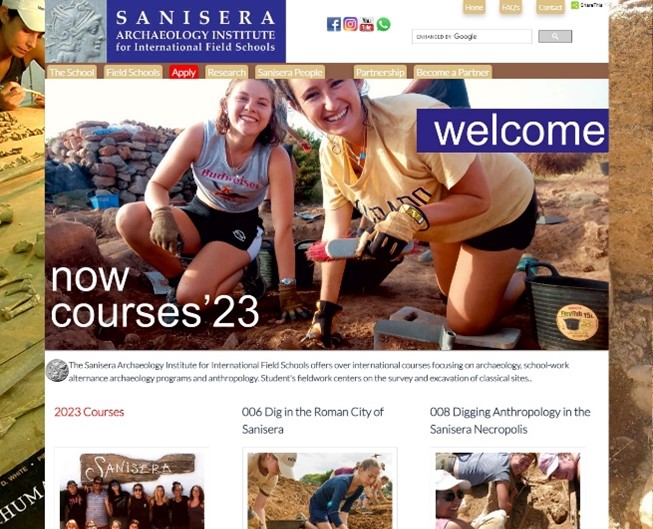

Some of these organizations grew large in scale, each was

trying to capture a niche within the field school market and attract as many

paying North American students as possible. Balkan Heritage Foundation focused on

the Balkans, offering dozens of programs across the region (Fig. 3). The Sanisera Archaeology Institute offered

programs initially at Palma de Mallorca and then expanded to offer programs

across Europe and the Middle East (Fig. 4). To maximize impact, these

organizations catered for both university students and general archaeology

enthusiasts, offering short programs (2-3 weeks) at low cost. In both Ireland

and the UK, a number of organizations were established, offering more

traditional, academic, long-format programs (Achil Archaeology Field School, Blackfriary Archaeology Field school, among others).

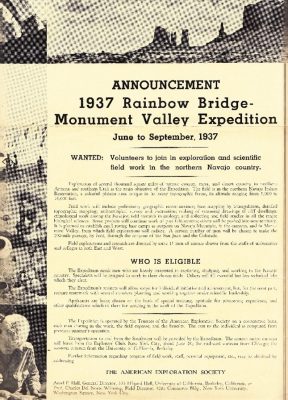

By 2006, the concept of field school aggregators reached the

U.S. The UCLA Field Program was the first attempt to aggregate several field

schools under one roof. That program combined emphasis on academics with the

economy of scale, offering students relatively affordable, high quality

programs. As successful as the UCLA Field Program was – and it was widely so –

its home in a public university proved to be too challenging and the program

closed in 2010. The UCLA program’s director – Ran Boytner – founded a new, independent

organization, the Institute for Field Research. For the first time, an

independent non-profit organization was using the power of the academic

peer-review process to ensure quality of both education and research. And given

that the IFR had low overhead cost, it was able to offer reduced-cost but high-quality

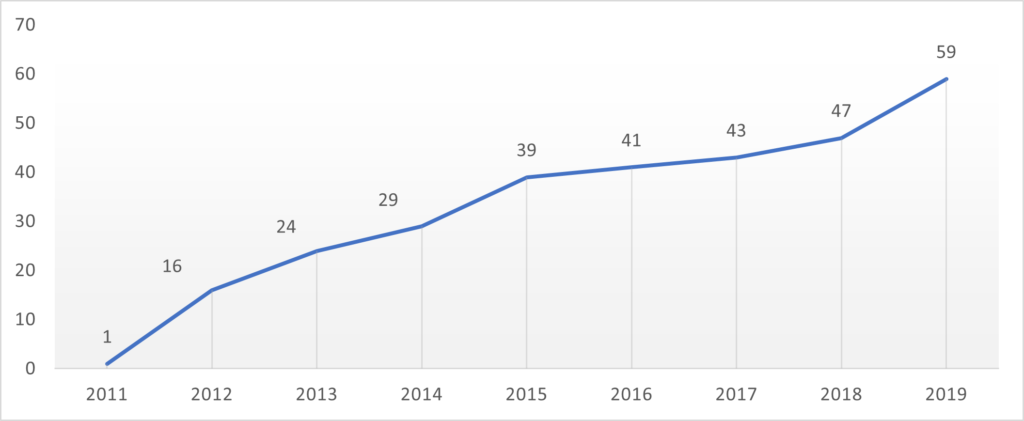

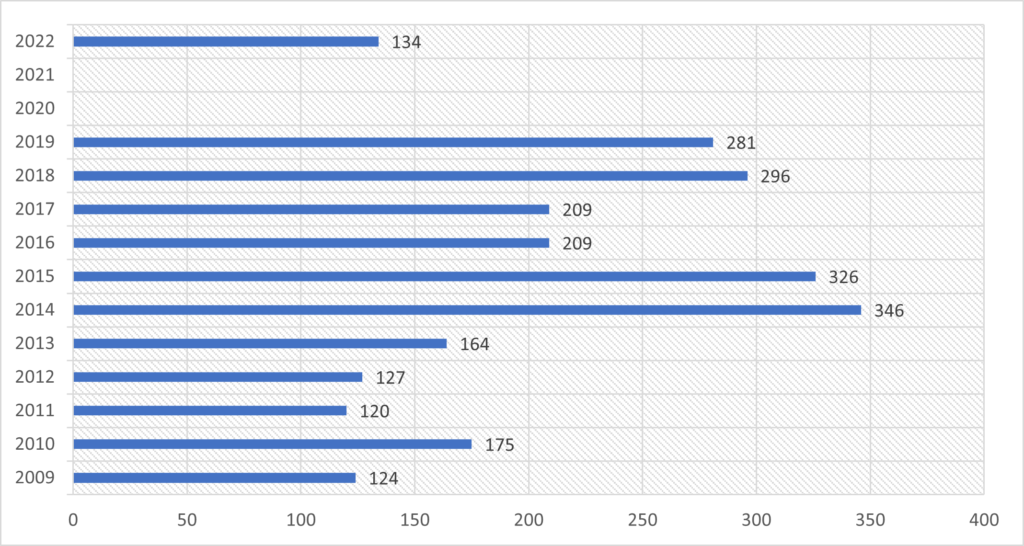

field schools. The IFR grew quite rapidly (Fig. 5) and became the largest

archaeology field school aggregator. By 2019, it was the fourth largest funder

of archaeological research in the US (after NSF, NatGeo and the Wenner-Gren

Foundation).

By April of 2020, all archaeological field schools across the world came to an abrupt halt. The COVID pandemic stopped all non-vital activity and for the following two years, few archaeology research projects, or field schools operated. As the world started recovering from the pandemic, archaeology – like all other aspects of post pandemic life – had to confront new realities.

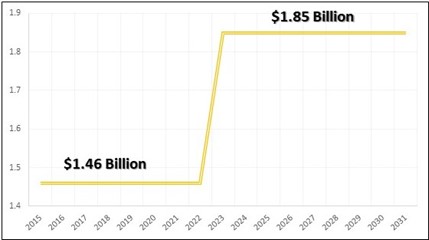

One of the most profound realities is that the number of archaeology majors in universities across the US is dropping (Fig. 6). The second is that the number of academic positions in archaeology is small and will likely start to shrink soon. As senior archaeologists retire, universities will likely replace only some and leave many positions unfilled. Third, the 2020 Great American Outdoor Act and the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is generating massive demand for Cultural Resource Management (CRM) professionals – the private sector side of archaeology (Fig. 7).

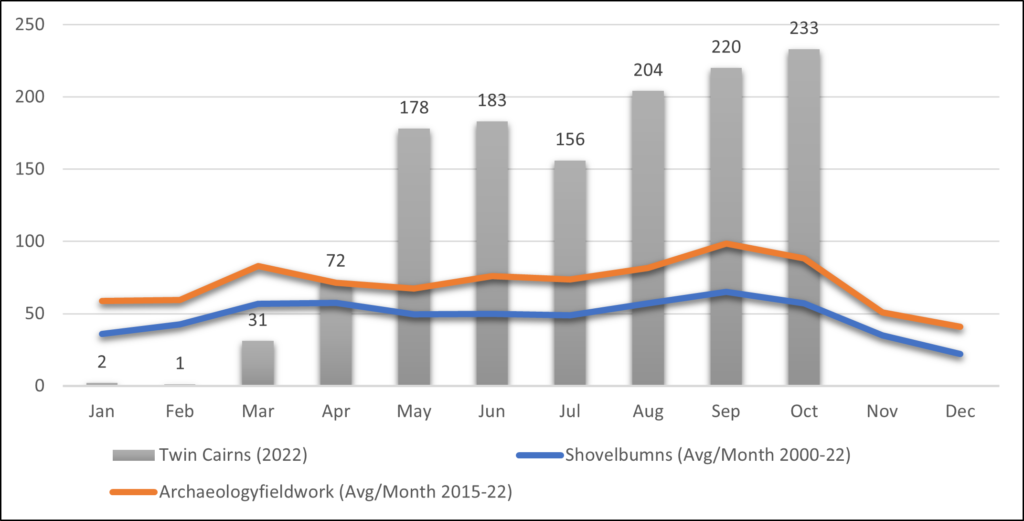

There is already a significant shortage of qualified professionals within the CRM workforce at all levels. As Daniel Sandweiss (President, Society for American Archaeology) wrote in the 2022 SAA October newsletter: “The CRM industry will play a larger role in the archaeology of the coming decades, even greater than the one that it already plays.” The demand for CRM professionals is at unprecedented levels and does not seem to be relenting anytime soon (Fig. 8).

The pivot to CRM training, while still maintaining high academic standards, has already begun. The Center for Field Sciences, established in 2021, is now offering programs that emphasize both academic and CRM career paths. In addition to research based field schools, each of the CFS programs adapts skills from the Skills Log Matrix™ – pioneered by Twin Cairns – in every syllabus. Other archaeological entities

Impacting such efforts, with yet unknown consequences, is the entry of Wall Street investment firms into the Cultural Resource Management sector. On Feb 15, 2022, PaleoWest – a large CRM firm – announced that the Riverside Company – a private equity firm – is investing in the company and its growth (Fig. 9). By Sep 26 of this year, PaleoWest announced its first major acquisition, merging with the Commonwealth Heritage Group (Fig. 10). This infusion of cash into a highly fragmented sector – there are over 1,300 CRM firms, none controlling more than 2% of market share – seems like a classical opportunity for equity firms to enter an otherwise untapped market, consolidate through Merger & Acquisition (M&A), and then offload these new entities at a much higher price point.

What impact would these very recent developments have on field schools? PaleoWest executives claim they wish to “professionalize” the sector. Will they begin investing in training, including in field schools, as part of such a push? Will they create their own internal training programs, replacing the general field school with a company specific training curriculum? Or, will they push for reduction in education and training for CRM employees so they may reduce wages and thus improve profitability? Joe Lee – Riverside Senior Partner – wrote in the press release published on the PaleoWest site: “Riverside is interested in companies that use technology to improve service quality and compete more effectively. PaleoWest exemplifies this strategy as their use of proprietary technology allows them to perform work more accurately and efficiently.” It is difficult to predict how all of these pressures will impact archaeology in general, or CRM and field schools in particular, as this Wall Street entry to the sector is new and unprecedented.

A different, but related concern across archaeology is that the explosive demand for CRM professionals will reduce work force quality and/or produce pressure on government agencies – both at the federal and local levels – to eliminate CRM compliance regulations so that infrastructure projects could be built without years of delay caused by CRM (and other) compliance issues. Twin Cairns reports that while the requirement of a bachelor or graduate degree for CRM positions is still strong (92% of all published positions require such degrees), the requirement of field school experience – traditionally a standard and basic requirement – dropped to only 51% in 2022. This reduction reflects the reality that very few field schools took place during the years of the COVID pandemic (2020-2021) and that the recovery of field school offerings is slow and does not reflect contemporary demand (Fig. 11).

While the CRM requirement for field school training is declining, the demand for those who do have such experience is increasing. CRM professionals with a field school experience command a higher salary. Moreover, the field school requirement for entry level government positions – well paid with significant benefits – is still strong. Almost all academic institutions require field school or extensive field experience as a condition to apply for graduate programs. It seems that an investment in field school training for individuals seeking long term careers in academia or CRM archaeology is worth the cost, today more than ever before.